The only time that nationalist Baloch leadership was accorded a chance to govern Balochistan was after the 1971 debacle – and that too grudgingly– as Ataullah Mengal took the reins of the provincial government on May 1, 1972, only to remain in power for nine months.

His government was cut short due to a number of challenges created by the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto-led central government in Islamabad.

Khan Abdul Wali Khan’s National Awami Party (NAP) and Mufti Mahmood’s Jamiat e Ulema e Islam (JUI) had swept the elections in 1970 in Balochistan and Northwest Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), respectively.

However, many factors contributed to them forming provincial governments after a delay of two years. One of the factors was the separation of East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, from West Pakistan as the popular Awami League was denied their right to form a government there. Meanwhile, Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) won by a majority in Sindh and Punjab while the NAP and JUI won by a majority in Balochistan and NWFP, respectively. But Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as President wanted stakes in the remaining two provinces as well.

Meanwhile, external influence also led to a late takeover of the provincial government by NAP since Iran’s Reza Pahlavi, who had friendly ties with Pakistan, feared that if the Baloch in a neighbouring country got the democratic right to rule, then they would demand the same on the Iranian side. When the Baloch resentment at the unjust dismissal of the Ataullah Mengal government and other injustices committed against the Baloch people resulted in the third insurgency that began on May 18, 1973 — with the killings of a ‘Sibi Scouts’ patrol of 8 men near Tandoori — Iran provided its helicopter gunships and pilots to Pakistan to help suppress the insurgency.

Finally, when NAP’s Ataullah Mengal formed a government in Balochistan, Punjab Governor Ghulam Mustafa Khar had ordered all the Punjabi officers serving in Balochistan to return to their province, subsequently crippling administration machinery in Balochistan.

The failure of administration machinery created a law and order situation in the province as evident from a December 3, 1972, Dawn report that states “an official spokesman said armed bands of Bugti tribesmen, reported to be moving towards Quetta… Some lawlessness is reported from Quetta also by some Bugti tribesmen in a bid to intimidate and harass the Provincial Government”.

Moreover, another provincial leader, Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti, had developed differences with the Mengal-led provincial government. Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti became the Balochistan governor after Ataullah Mengal’s government was dismissed nine months later.

Simultaneously, there were some minor incidents of confrontations between the Marri tribesmen and settlers (Punjabi). However, these incidents were falsely portrayed to be grave threats to the security of Punjabis residing in Balochistan by the central government, and Frontier Corps personnel were deployed in the province under the garb of security provisions.

When this unrest fizzled out, the central government entrusted their longtime ally Jam Ghulam Qadir of Lasbela to create a situation that would prompt NAP’s dismissal.

A January 27, 1973, Dawn report states, “An armed rebellion has started in the Lasbela district, about 60 miles from Karachi across the Hub river, since yesterday [Jan 25], by 400 to 500 riflemen and fighting is going on between them and the men of the District Levies and the Militia”.

Subsequently, the central government had taken over the law enforcement agencies which refused to act against the miscreants. This led the Ataullah government to form a Levies force to counter the miscreants. However, the Centre termed the Levies force a “Lashkar” and eventually, the army was sent to the province to curtail the ‘violent situation’.

On January 31, 1973, the Centre issued a communique that army units were being sent to Balochistan at Governor Bizenjo’s request. However, on February 1, 1973, Bizenjo denied that he had ever requested army units, saying “the law and order situation in Lasbela district is totally under control”.

A February 7, 1973, Dawn report exposed the intentions of the central government, as the report said “units of the Armed Forces have been moved into Balochistan to help the provincial government maintain law and order, Interior Minister Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan disclosed to newsmen..” The units, he said, had been sent to prevent clashes between the armed Lashkars of Mengal, Bizenjo, Brohi, and some other tribes of Balochistan and the people of Lasbela”.

These series of events were a prelude to the impending ‘Iraqi Arms Find Saga’ which was being meticulously plotted out to ensure the Ataullah Mengal government’s dismissal.

Finally, on February 10, 1973, with a host of foreign and local journalists, a raid was conducted on the residence of the Iraqi military attaché Nasir Al-Saud, who had conveniently left Pakistan three days earlier. The cache of 300 Soviet submachine guns and 48,000 rounds of ammunition was unearthed and interestingly a shipment of some more arms in diplomatic baggage arrived from Karachi that evening and that too was, naturally, nabbed.

Selig Harrison, in his book “In Afghanistan’s Shadow: Baluch Nationalism and Soviet Temptations”, has claimed these arms were detected in Karachi but were allowed to go to Islamabad to maximize the sensational impact and provide grounds for dismissal of the Ataullah government which was already being accused by Bhutto of repeatedly exceeding constitutional authority.

After the recovery of a large amount of ammunition, Bhutto also accused the Ataullah government of colluding with Iraq and the Soviet Union in a bid to dismember Pakistan and Iran.

Rafi Raza, who was a minister in the Bhutto cabinet at that time, told me in 2015 that the government knew about the arms arriving in Karachi and waited until they were delivered to Islamabad. He said when he came to know that the raid was conducted with “fanfare”, he had felt that the government had bungled the job by trying to sensationalise it.

Another interesting outcome of this saga was the resignation of my paternal uncle Mir Rasool Bakhsh Talpur as the Sindh Governor.

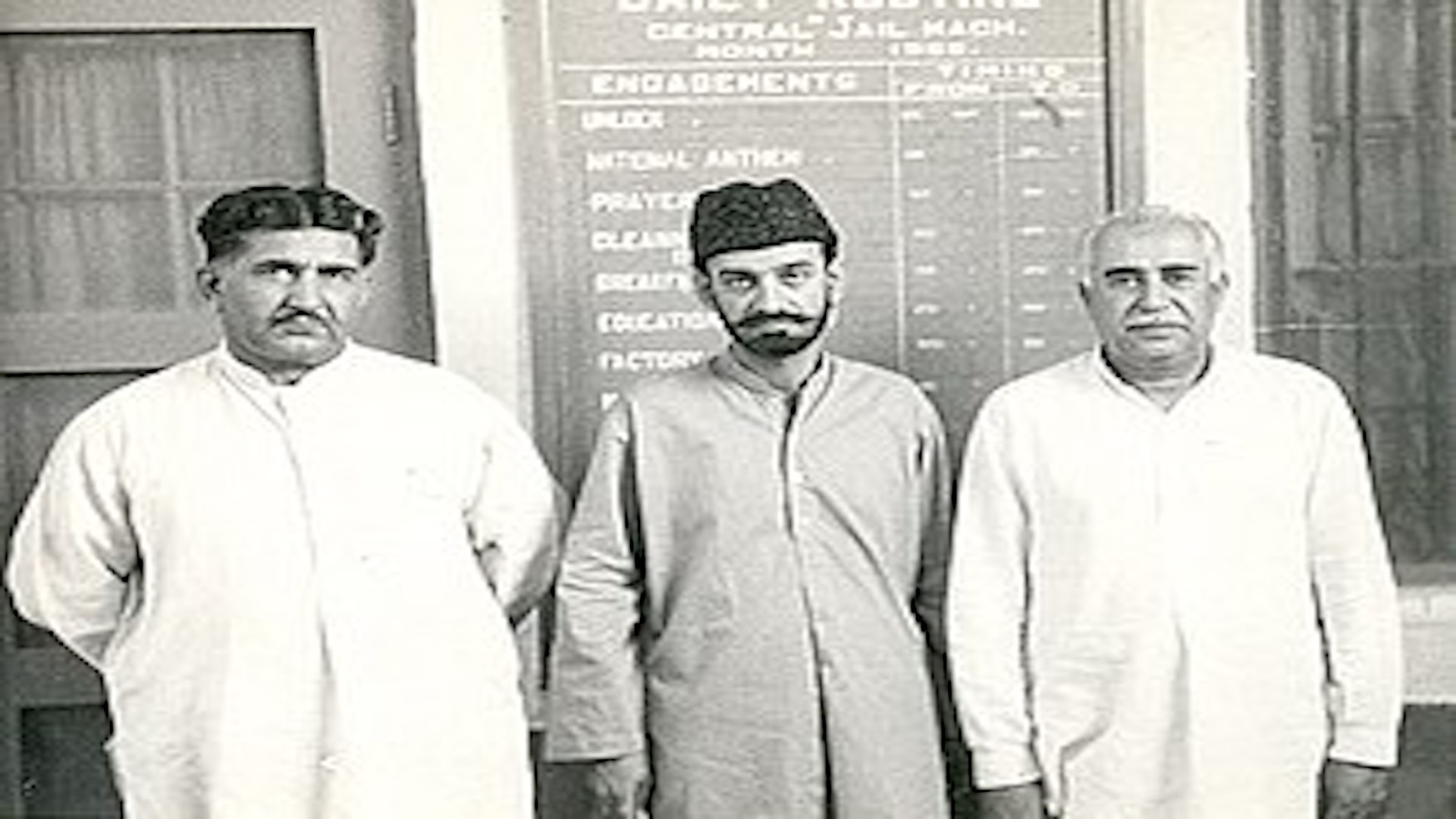

He resigned because Jam Sadiq Ali, a Sindh minister, alleged that my father Mir Ali Ahmed Talpur was involved in this Iraqi arms saga because I “was in Balochistan Hills training as a guerrilla”. I was indeed in the Marri Hills at that time along with other members of the “London Group” namely Mohammad Bhabha, Asad Rahman, Ahmed Rashid, Duleep Dass – while Najam Sethi and Rashed Rahman were liaising in the cities.

Mir Sahib resigned at a press conference where someone asked whether he was mindful of the consequences of opposing Bhutto. He replied: “We have seen many others. I am not worried.”

The above is the story of the series of events that led to the ‘Iraqi Arms Find’ saga and how the entire saga unfolded.

It’s Pakistan’s security apparatus alone that has been deciding what happens in Balochistan since 1948, much to the detriment of the Baloch men – and now women too – who keep getting abducted and killed at a whiff of suspicion.

The main question remains: how could the Baloch have transported these arms from Islamabad to the hills of Balochistan? It would have been risky for anyone to do it. The three days prior departure of Nasir Al-Saud is further proof that this episode was staged to oust the Ataullah Mengal government.

Amid the entire saga, all the stakeholders involved failed to understand that an opportunity for mainstream Baloch nationalist leadership was forever lost, and not to mention this dismissal created an unbridgeable chasm of mistrust between the Baloch people and the State.

Unfortunately, it’s Pakistan’s security apparatus alone that has been deciding what happens in Balochistan since 1948, much to the detriment of the Baloch men – and now women too – who keep getting abducted and killed at a whiff of suspicion.

The state must understand that its policy in Balochistan for the past 75 years has failed, and future policies would be met with the same failure. There will always be enough conscionable Baloch committed to the rights of the Baloch in Balochistan. These defenders of the Baloch people’s rights will remain a thorn, not only on the side of the Pakistani state but also China, which too, wants to benefit from the Baloch resources.

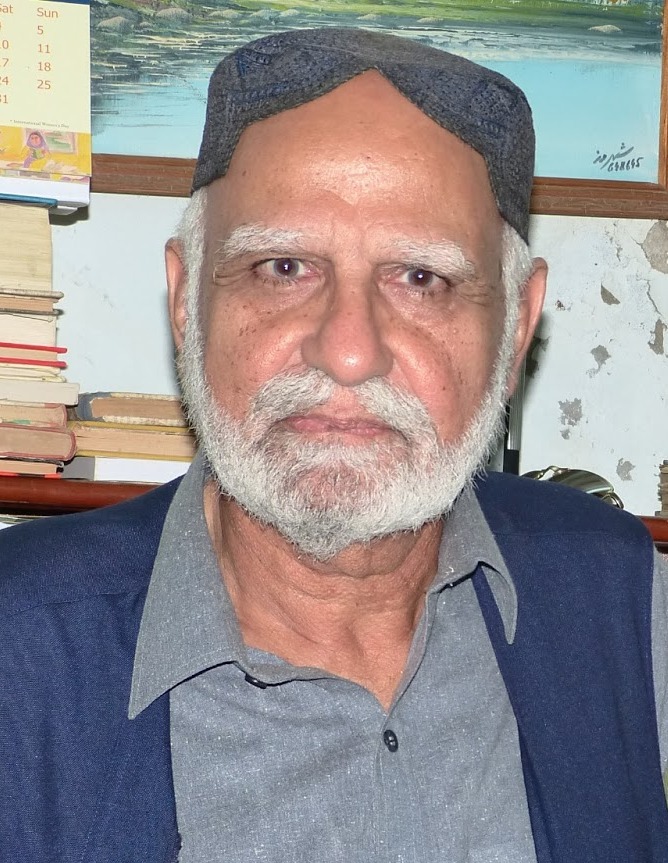

The writer has been associated with the Baloch movement since 1971. He tweets @mmatalpur and can be reached at mmatalpur@gmail.com.