This article is part of a series titled “Is there a way forward for Pakistan?” Read more about the series here.

Goldman Sachs caused a stir when it said that by 2075, Pakistan could become the world’s sixth-largest economy. Most other prognostications of Pakistan are grim.

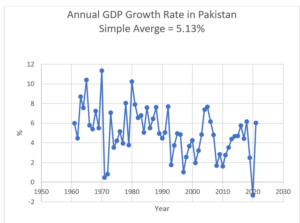

During the 75 years that have elapsed since its birth in 1947, Pakistan has exhibited a volatile pattern of economic growth. Episodes of military and civilian rule mark its history.

Pakistan is a victim of elite capture. It’s the surprising omission in the book, Why Nations Fail? It contends that countries fail where elites freely extract economic rents, property rights are weak, there is no respect for rule of law, and a large underground economy. The population has no incentive to innovate and invest because their gains are seized by the state, which creates a vicious cycle.

Countries with “extractive” economic and political institutions remain poor, while those with “inclusive” institutions lift their people out of poverty. Inclusive institutions have representative legislatures, good public schools, open markets, and respect for intellectual property. These countries invest in infrastructure, educate their populations, and fight poverty and disease. Their open intellectual environment encourages innovations and attracts foreign capital.

The authors discuss the case of North and South Korea, which were two split 80 years ago. The North went the way of communism while the South embraced markets and eventually democracy.

In sub-Saharan Africa, Congo ranks at the bottom while Botswana ranks at the top. Congo suffered because it was in the grip of a self-centered, exploitative dictatorship. Botswana focused on developing inclusive institutions, held regular elections, enforced property rights, and never had a civil war. People were happy because the governing elite voluntarily valued the public interest over private greed.

In the US, a century after the civil war, the south remains relatively poor compared to the north because the institutions in the north were inclusive while those in the south were exploitative, with slavery being its most dominant manifestation.

A history marred by institutional failure

Institutional failure permeates Pakistan’s history. In the beginning, civilians governed poorly. In 1958, the army seized power, economic growth picked up and political stability was imposed. Pakistan entered into defense agreements with the US, which gave it significant amounts of aid. In 1965, Pakistan blundered into war with India. A new political party emerged on the scene with a socialist agenda.

A coup within a coup occurred in 1969, general elections were held in 1970, and but the results were annulled in 1971, leading to a civil war and the secession of the East in December.

The military handed over power to a civilian government. A wave of nationalizations followed and the economy stalled, creating a political crisis. The military seized power. In this third episode, the military governed for 11 years, political stability was enforced, the army aligned itself with the US, and foreign aid began to flow in. Economic growth resumed. Military rule ended when the ruling general died in a plane crash.

Another period of the civilian rule followed, but economic growth was uneven. It ended in 1999, when the army seized power. In this fourth episode, the economy began to grow as political stability was enforced and foreign aid began to pour in. In a few years, terrorist attacks unleashed a crisis of governance, an emergency was declared, and ultimately the military ruler resigned. Since then, civilians have ruled.

India had lagged behind Pakistan in its economic growth rate but that relationship flipped in 1999. More tellingly, Bangladesh moved ahead of Pakistan, even though East Pakistan had lagged behind West Pakistan since independence.

Pakistan’s GDP growth has been declining since 1961.

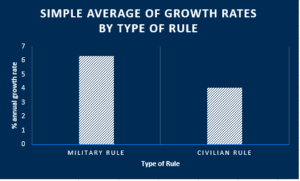

The data also show that economic growth has been higher under military rule than under civilian rule.

Unlike the experience of Asian Tigers, military rule in Pakistan has been unable to institutionalise economic growth. Nor has it yielded quietly to civilian rule. Pakistan’s long-standing rivalry with India, and its frequent involvement in wars in Afghanistan, have given the military the excuse it needs to stay in power.

The situation today

Institutional failure continues to pervade Pakistan. The economy has been teetering on the brink of bankruptcy for months. Inflation is at an all-time high. The trade and budget accounts are in the red. Foreign debt has broken all records. The number of months with which the country’s foreign exchange reserves can cover imports continues to shrink. The currency is in free fall.

Traditional allies such as Saudi Arabia are reluctant to lend money to Pakistan. The IMF has presented stringent conditions before it will make the next loan.

The power grid has become increasingly unreliable, as was seen in January when the entire nation went dark.

Last year’s floods devastated the lives of millions. Their full effect has yet to be felt, and will only become evident once this year’s crop production is measured.

Politically, the country is in the grip of one of the worst crises in its history. The ruling coalition and the opposing party, which was in governance until April of last year, don’t see eye to eye on any issue. Name-calling, arrests, tortures, murders, and mass rallies are an everyday occurrence. Behind the scenes, the military is holding its cards close to the chest.

On the foreign policy front, relations with India continue to be strained. Pakistan continues to spend a large amount of the budget on defense, being locked in an arms race with India, which encompasses both conventional and nuclear weapons. Relations with Afghanistan are tense since many of the terrorist attacks in Pakistan can be traced to groups affiliated with the Taliban which govern Afghanistan.

Why is Pakistan failing?

Its poor economic performance is driven by weaknesses in the structure of its economy. Its key economic indicators — such as the ratio of savings and investment to GDP, the ratio of taxes to GDP, and the ratio of exports to GDP — are much lower with those for India and Bangladesh.

Corruption and nepotism are pervasive, and not just at the level of the elite. They are visible at every level from the peon on up. That’s notwithstanding the fact that religion is embedded in the social and political fabric of the country.

In the late 1960s, a populist leader weaponised poverty by asserting that every person is asking for “bread, clothing, and shelter.” His ideology of Islamic Socialism failed to deliver. He was himself part of the elite.

In 2018, another populist leader appeared offering to create a new Pakistan which would combine the best elements of Islam, Socialism, and Democracy. He claimed he would rid the country of the corrupt leadership of the two parties that had governed the country since 1988. He promised he would not borrow any money from abroad.

He also failed to deliver and lost a vote of no confidence in parliament before he had completed his term.

The current government is composed of the two parties that he had derided. They inherited a mess but instead of solving it, they have deepened it. The country is now on the brink of ruin. The former prime minister is drawing very large crowds throughout the country and has weaponized religion by adopting a verse from the Opening Chapter as his motto.

Between false messiahs and the army

Pakistan suffers from an abundance of false messiahs. And it suffers from the constant interference of the military in politics. No one can challenge the generals. Every army chief presents himself as being indispensable for the survival of the country. Two recent books challenge the army’s performance on the battlefield and question its larger-than-life role in national and international affairs.

Twenty years ago, in a similar vein, I published Rethinking the National Security of Pakistan. From a national perspective, I was right. But I was wrong from the viewpoint of the generals.

A way has to be found for the elite to give up their franchise. A way has to be found to get the landlords to divide their estates. A way has to be found to get the multi-millionaires to start paying taxes. And a way has to be found to force the army to step down from the commanding heights of the economy.

In other words, a way has to be found to change the national culture of Pakistan and only then will the country exit the elite capture syndrome.

A way forward

If the economy continues to teeter on the cliff and the political standoff between the governing parties and the main opposition party continues, the country may descend into chaos and anarchy.

Historically, in situations such as these, the army seizes power. This time, the army does not appear to be in a position to seize power because the former prime minister has managed to turn much of the nation against the military. The army is paralysed into inaction. A few former generals are vocally criticising the army, which is without precedent.

If the army won’t take over and elections won’t be held, the situation may implode with riots, widespread looting, robberies, murders and assassinations, and a total breakdown of law and order.

That may cause the elite to flee the country. A revolution may take place. A new leader may emerge who can begin the task of transforming the country. If the new leader is cut in the cloth of a Lenin or a Mao, that won’t bode well for the country. If the new leader is cut in the cloth of a Khomeini, that won’t bode well for the country either.

If the economy continues to teeter on the cliff and the political standoff between the governing parties and the main opposition party continues, the country may descend into chaos and anarchy.

But three good outcomes are still possible.

First, a sincere and competent individual may take the helm and begin the task of transforming the nation’s culture.

Second, the elite may have a change of heart, realising that the days when they fleeced the country and called the shots are over.

Third, and this is the least likely scenario, elections will be held later this year, returning Imran Khan to office. He may have an epiphany and govern as an enlightened man, finally delivering on the tall promises he made in 2018.

If one of these scenarios comes to pass, then Pakistan can get back on the road to development. This will be a complex task that will take many years and encompass many dimensions that span the political, social, cultural and economic spectrum.

Reviewing the example of other countries that have turned themselves around, the reform agenda will encompass eight steps.

First, the authority of the state will have to be re-established. Before that can be done, the leadership will have to earn the people’s trust.

Second, new economic policies will have to be implemented which reduce poverty, increase social cohesion, and create the conditions for long-term stability.

Third, infrastructure will have to be rebuilt, including the power grid, telecommunications, water, sewage, roads and bridges.

Fourth, the police force will have to be reconstituted with a focus on enforcing the law, promoting human rights and eliminating corruption.

Fifth, the educational curriculum will have to be modernised so it can promote a culture that values honesty, respect for diversity, tolerance for differences of opinion and thus shape the creation of a more inclusive society. Female participation in education should be encouraged because ultimately women can play a great role in enhancing the productivity of the country’s workforce.

Sixth, the media would be encouraged to help change the culture of the country by promoting gender equality and diversity of languages, traditions and religious beliefs, and learning from other countries.

Seventh, legislation should be passed that prohibits discrimination based on gender, race, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation.

Eight, national participation in arts and culture should be encouraged through exhibitions, concerts and performances that celebrate differences in opinions, beliefs and languages to promote understanding and national harmony.

If these eight conditions are fulfilled, Pakistan will get back on the road to recovery and take its rightful place in the comity of nations.

The writer is an Economist-at-Large based in the US. He has been writing political commentary since 1986 and has authored or edited three books on Pakistan.