Nearly all nation-states actively try to discourage diversity and the right to be different. No discourse on diversity is allowed in mainstream narratives, and a false sense of uniformity is forced upon people. History is replete with the horrors perpetrated by these dominant actors in attempts to create uniformity through both subtle and brutal ways.

This could lead to a conflict with dominant actors as we have seen it happening in the case of Bangladesh and Balochistan. Historically, this forced uniformity didn’t bode well either for Pakistan or for the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, as they broke up.

For creating conditions for uniformity, the state first disenfranchises the recalcitrant nations politically by installing pliable politicians who act as the henchmen of the dominant nation, trying to give people a false sense of representation, but this ploy doesn’t make much headway as people see where the real power lies. In Balochistan, there have been so-called representative governments that have only furthered Islamabad or rather Rawalpindi’s interests there. Secondly, the imposition of uniformity on a minority is invariably connected with the economic interests of the dominant. Corporations and predatory countries are given free rein to exploit their resources to keep people in penury busy eking out lives.

The forced accession of Balochistan on March 27, 1948, followed concerted efforts by Pakistan to erase the Baloch identity by force. Pakistan has always tried to force “patriotism” by undermining nationalistic sentiments in the province. This was resisted by the Baloch people, as were consequent injustices, as they drew inspiration from strong Baloch political leaders. People resisted not only the subtle overtures but also the persistent brutal assaults that became the norm in Balochistan.

The State has allowed and empowered religious groups and madrassas to proliferate in Balochistan, hoping that religion will change or at least dilute the nationalist sentiments.

In Balochistan, these unfortunate attempts at imposing uniformity have led to an open conflict. In the last two decades, systematic enforced disappearances, which have a long history, have affected a broad spectrum of Baloch society. This practice of enforced disappearance became more rampant when the state saw its policy of imposing uniformity by subtle means fail. With the passage of time, brutalities have intensified with more and more educated Baloch people falling victim. The state doesn’t realise that increased repression leads to more resistance from people who value and cherish their historical, political, and cultural legacies.

The state has allowed and empowered religious groups and madrassas to proliferate, hoping that religion will change or at least dilute the nationalist sentiments. Sadly, religion here has complemented repressive forces. A report stated there are more than 10,000 small and big madrassas in Balochistan, which roughly translates into the availability of one madrassa for every 1,200 to 1,300 people in the province. In Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, by contrast, there is one madrassah for about 45,000 to 50,000, and 10,000 to 12,000 inhabitants, respectively. This high number of madrassas in the province would not have been possible without active state patronage.

Moreover, the state-sponsored ‘death squads’ in Balochistan have belonged to radical religious outfits. Religion was weaponised to coerce the Baloch people into submission and target the Hazaras.

In times of tragedies and disasters, people are psychologically, emotionally, and physically vulnerable, and those anxious to impose uniformity rush in to exploit this vulnerability. Pakistan has always used this opportunity along with its religious extremist backers to force uniformity and to break the will of the Baloch people by trying to undermine nationalistic sentiments.

The forced accession of Balochistan on March 27, 1948, followed concerted efforts by Pakistan to erase the Baloch identity by force. Pakistan has always tried to force “patriotism” by undermining nationalistic sentiments in the province.

On September 24, 2013, when Awaran was reeling from the shocks of the long-drawn army and Frontier Corps operations to contain the unflinching resistance of Dr Allah Nazar, it was hit by a 7.8 magnitude earthquake. The UN humanitarian envoy, Dr Abdullah Al-Matouq, offered assistance, but Pakistani authorities declined it. Independent sources confirmed the relief supplies being sent by individuals and NGOs were stopped by the Frontier Constabulary (FC), which said only it would distribute them. Shahzeb Jillani of BBC reported then that in Teertej village just outside Awaran, 95 percent of houses had collapsed, 22 people died and many survivors had suffered fractures, broken arms, ribs, and head injuries. The villagers told him that some 48 hours after the disaster caused by the earthquake, Pakistani soldiers arrived with a truckload of tents and food supplies, but the locals turned them away. A villager said, “We told them we did not want anything to do with them.” The people there and the army were two warring parties then – due to decades of irresolvable animosities nurtured by rampant injustices. Ironically, those who had terrorized people in this manner wanted to appear as benefactors.

The State doesn’t realise that increased repression leads to more resistance from people who value and cherish their historical, political, and cultural legacies.

Mahvish Ahmad, then reporting for ‘Dawn’, was in Mashkay on 15th October 2013. She writes: “It was 6 O’clock on Monday morning as this correspondent suddenly woke to the loud sounds of explosion in the otherwise sleepy town of Mashky-Gajjar, as the army troops entered the town centre to take control where the Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF), a banned separatist militant group, had been quite active and in recent weeks many separatists organizations had remained involved in helping thousands of quake-affected residents”.

The disaster was taken advantage of to secure its interest which the army had, otherwise, been unable to gain.

Regarding the attitude of state authorities towards the Baloch people in the aftermath of disasters, it seems the authorities do not want to provide them relief but rather punish the Baloch people for not submitting to the “imposed uniformity”. For instance, on June 25, 2007, Cyclone Yemyin battered Balochistan, affecting at least 10 districts of Balochistan and four districts of Sindh, disrupting the lives of at least 1.5 million people and killing more than 2 million livestock, worth over 4 billion rupees. Despite the magnitude of the disaster, then prime minister Shaukat Aziz in July 2007, announced that “Pakistan will not take foreign aid from any country to overcome the losses and devastation caused by Cyclone Yemyin in Balochistan”.

Similarly, Cyclone Phet wreaked havoc in Gwadar, Pasni, and other coastal towns on 6 June 2010. Hundreds of fishing boats went missing, thousands were displaced, innumerable properties were damaged and some 19,303 families were affected – all of this in spite of previous warnings of a cyclone by the United Nations which were ignored. Relief was slow and sketchy.

The Baloch people have to bear the worst of both worlds as Pakistan has unrelentingly tried to obliterate the Baloch identity in the name of religion and ‘one nation’ while disregarding Balochistan’s old history and culture. Meanwhile, the State does that with the connivance of self-interested Baloch politicians, who it seems are more loyal to the king than the king himself. They have tried to achieve this “uniformity” through brutal means.

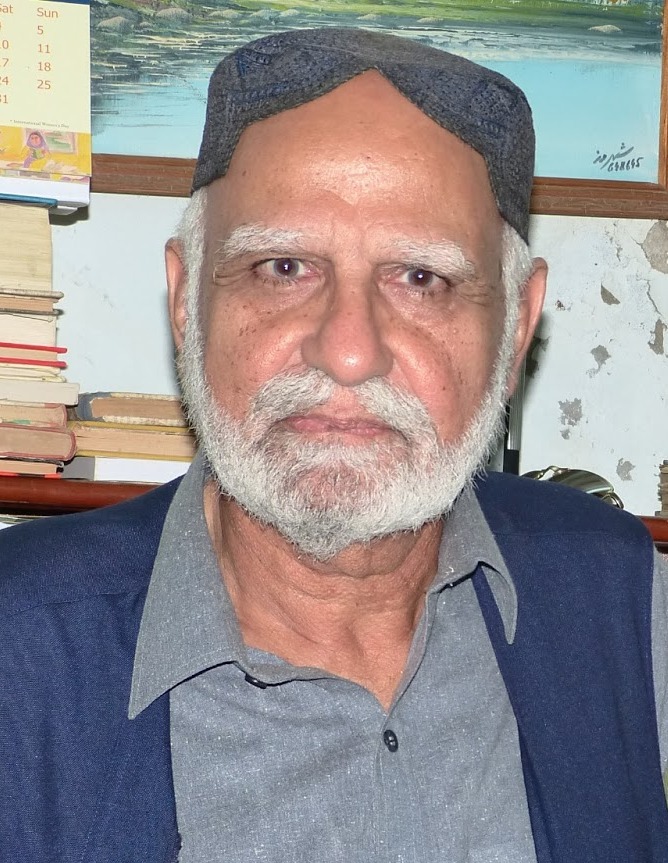

The writer has been associated with the Baloch movement since 1971. He tweets @mmatalpur and can be reached at mmatalpur@gmail.com.